|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

Call me a heretic, but I’m not sure I really want to ‘own my own data.’ I’m not too sure what data is mine anyway, and I don’t actually care if a business uses my search queries to target ads at me.

Those ads might even, as Google or Facebook like to claim, be more interesting because they are targeted. In practice, of course, they’re usually not. In fact, they’re often completely pointless because they’re advertising something I recently bought—the one thing I will not be needing for a while.

But on the bigger point, is Silicon Valley’s data-selling model really so offensive? It’s often cited by blockchain entrepreneurs as the ‘pain point’ that their business idea is designed to solve. But I’ve never been convinced that most people are as worried as these startup founders believe they are.

If I think of the businesses that I’d like to see improving, the list would include ISPs, with their poor service and high charges, airports, with their inefficiencies and stranglehold over their users, and railways, which also have passengers at their mercy for lack of alternatives.

What do all those businesses have in common? Well, the fact that they operate without a competitive marketplace to keep them on their toes.

If we look at the businesses that seem to work well, like supermarkets, airlines, and online shopping and delivery, they all operate on tiny profit margins in cut-throat markets. The good news is that these businesses are trying to cut each other’s throats, not ours, and they do so by offering us a better service.

So, to continue my heresy, I think the giant Silicon Valley tech companies are more similar to the businesses that work well than ones that lock in their customers and don’t have much competition.

Yes, I hear you say, but aren’t Google, Amazon, Apple, and Facebook effectively monopolies—so big that it would be impossible for a competitor to usurp them? To some extent, I’d have to admit that, and they do have a nasty habit of buying up promising potential competitors like Instagram or Whatsapp before they have a chance to compete.

But there is still an awesome ‘battle of the giants’ between them. Look at Google’s worries about AI providing an alternative to search engines in a way that makes Google’s ads a thing of the past. And if Silicon Valley was a land of entrenched powers, how did OpenAI become such a big player so fast (albeit with the help of Microsoft’s massive investment power)?

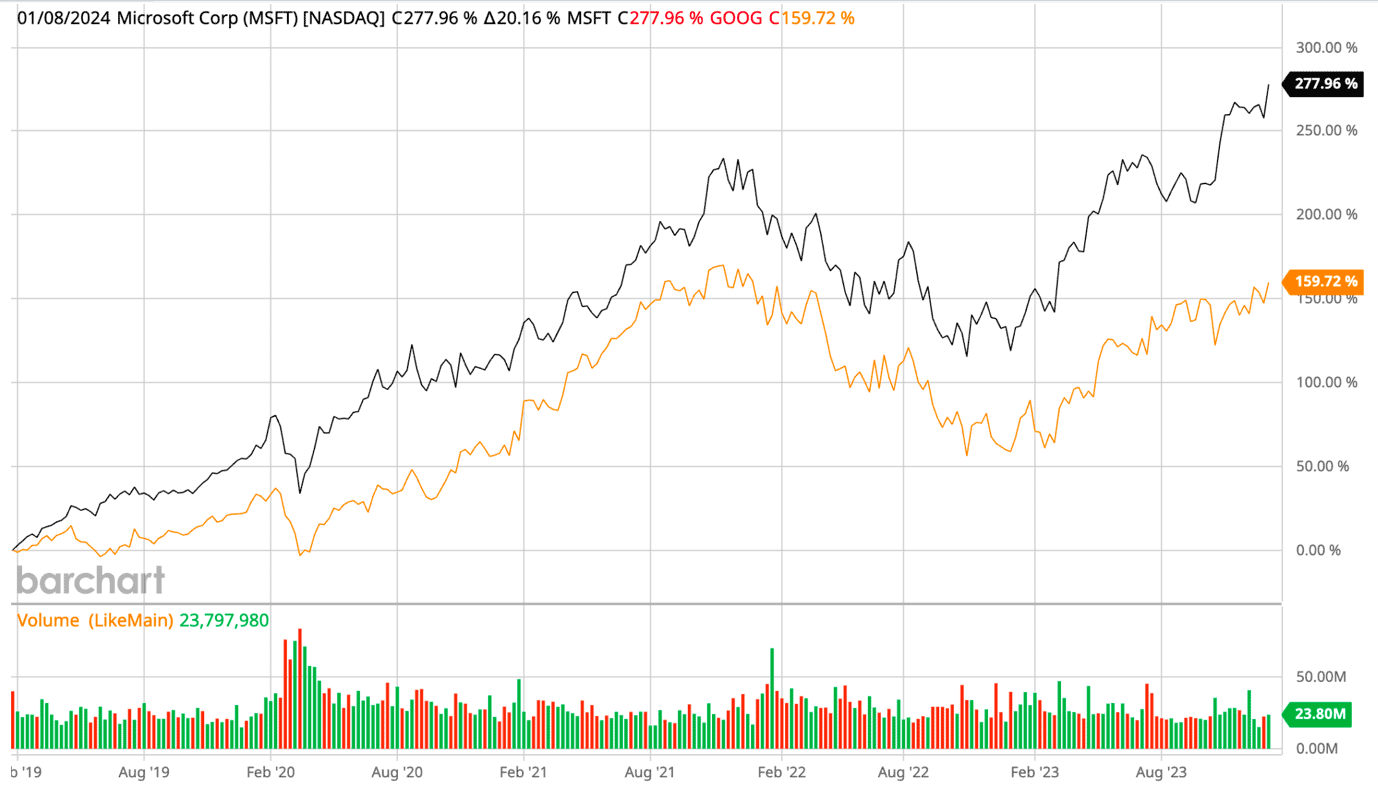

Talking of Microsoft, it was being written off a few years ago: the Windows cash cow was in long-term decline, Bing wasn’t getting traction, and Xbox was not for the cool kids. But look at it now: they bet big on cloud storage, gaming, and AI, and you’d have done better five years ago putting your money into it than into Google (although you’d have done very well with either):

Silicon Valley has more money than it’s possible to imagine, but it’s hardly a stable seat of power. These giant businesses are in a daily life-and-death struggle with each other, and the outcome is far from predetermined.

In 2013, the acronym FANG was coined to represent the tech giants—Facebook, Amazon, Netflix, and Google. This month, Forbes introduced a new acronym: MAMAA – Meta, Apple, Microsoft, Amazon, Alphabet. So that’s not just new names (Meta and Alphabet) but new (or returning) giants Microsoft and Apple—with Netflix kicked out.

Arguably, today’s list should include AI winners NVIDIA (MAMAAN?). Or, if there’s room for one more, the latest idea is ‘The Magnificent 7’—Apple, Microsoft, Alphabet, Amazon, Tesla, Meta, and NVIDIA. Or, as I prefer to call them, MATAMAN. In Silicon Valley, the times, they are always a-changing.

So what’s that got to do with sharing my data? Well, I still believe there’s merit in an old argument that Google put forward against accusations that it was a monopoly: that its customers are always only a click away from being able to switch to a competitor. It’s not really Google’s fault that, like Facebook or eBay, it benefits from a ‘network effect’ – the more people use it the better its service becomes.

It’s the ad model that makes the defense against monopoly possible. Because Google is ‘free’ to use, we are not locked into financial arrangements with it. OK, you can be if you want some of its services now, but for its flagship product Google ‘sells our data’ to its advertisers—and that’s the problem, say those blockchain entrepreneurs. In the future, they say, we’ll be able to sell information about ourselves to whoever we want and have ‘complete control’ over what happens to it.

I’m sorry, but I just can’t see that happening. Even if I could find someone who thought they could make money from knowing what Internet searches I’d made or what time of day I logged on, could I be bothered to set up a payment system so that I’d be paid miniscule amounts of money in return for the information? The only way those payments would add up to enough to buy the proverbial cup of coffee would be if I did some kind of ‘bulk deal’ to a business to sell everything about me. Then, they’d analyze it and sell different bits of it to other people. Bingo! Once again, I wouldn’t know who knew what about me, and I’ve lost control of my data.

No, just as I don’t charge people to know where I live or for seeing me going into the supermarket or what I buy when I’m in it, I don’t, in principle, mind if businesses that are providing a free service gather information about my online behavior. And if that means that the tech giants are more keenly focused on keeping me happy than, say, my useless ISP, then that seems a price worth paying.

Let me end with a coda about where I do think blockchain businesses can offer a valuable service with ‘my data.’ Catherine Lephoto of VX Technologies told me about work they are doing to allow individuals to curate validated qualifications from educational institutions so that if you want to apply to a university or for a job, you can send access to authenticated documents with your application. You would no longer have to rely on attachments that could easily be falsified, and the recipient could cut out time-consuming checks to make sure you are telling the truth. That makes a lot of sense. It requires the provider of the qualification to sign up to the system, but they would have the incentive of not having to answer so many questions from people wanting to confirm the qualifications they have issued.

Perhaps the moral of the story is that there’s data, and there’s data. Some are valuable (my degree certificate) and worth my looking after. But for the rest, well, help yourself—and keep providing those free services, please.

Watch: Decentralization is pushing data to the edges

07-02-2025

07-02-2025