|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

Since its inception, Bitcoin has not only revolutionized the way we think about money but also brought about a paradigm shift in understanding the intersection of technology, finance, and human interaction. At its core, Bitcoin is more than just a digital currency; it’s a complex yet imperfectly designed system that inherently necessitates human participation. Bitcoin’s critics have long criticized using race conditions to come to a consensus or the lack of cryptographic finality. Indeed, even the greats have criticized Bitcoin’s lack of cryptographic anonymity and many other “faults” with Bitcoin.

Looking at ways to add more anonymity to bitcoin

— halfin (@halfin) January 21, 2009

Understanding Bitcoin’s design

At its heart, Bitcoin is just a distributed timestamp server that writes to a distributed database. This means that, unlike traditional currencies managed by central banks, Bitcoin operates on a network of computers, each contributing to a shared public ledger known as the blockchain. This ledger records all transactions, ensuring transparency and security. However, it’s in the nuances of its implementation that Bitcoin reveals its intentional imperfections, and due to the distributed nature of consensus, many people have assumed it was a sort of competitive democracy. I think this is false, but if you’re reading my work, you probably already know that!

Hard money doesn’t change, but that doesn’t mean that the ways it is implemented cannot be optimized. For example, gold was the same 10,000 years ago as it is today, but today, much of its value comes from its use in manufacturing computers and other high-tech devices.

Intentional imperfections in software implementation

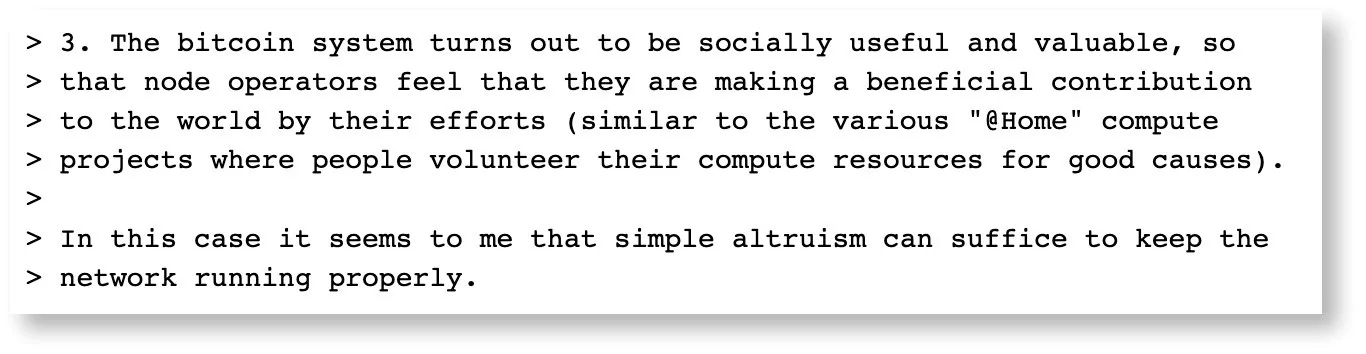

Bitcoin’s seeming imperfections are not flaws in the traditional sense but instead carefully crafted elements that encourage human engagement. For instance, the process of mining Bitcoin requires significant computational power, making it permanently competitive. I promise I’m not picking on Hal, but he contended that everyone should run a node and that Bitcoin’s consensus should be altruistic. This was covered in my article about why Hal Finney isn’t Satoshi Nakamoto. Still, the purpose here is to explore why geniuses like Finney and many other people don’t understand the beauty of Bitcoin’s imperfections.

Here’s Finney on Bitcoin nodes…

This shows the desire to build a pre-planned mechanism for finality instead of competitive consensus, and it is the underlying thought that created “user activated soft forks” or “UASF,” and the entire notion that home nodes matter at all. By applying Finney’s ideas, there grew a desire to solve the Byzantine Generals’ problem with Byzantine soldiers born from the unending fear that competitive consensus can’t really work at scale, and even if it could, it is somehow undesirable.

To clarify, the Byzantine Generals problem is about the trustworthiness of key communication channels and achieving trust under the presumption of duress. Bitcoin solves this with proof of work and the competition created by the difficulty adjustment. We don’t have to trust people if they are willing to lead with proof of work before asking us to accept their version of the updated ledger.

But to home noders, they don’t think they can ever trust the proof of work, so they must also engage in the system as a sort of soldier and double-check everything themselves. Essentially, they think Satoshi was wrong; Bitcoin’s solution for trust was insufficient and, therefore, must be remade in the image of the Byzantine soldier, who just so happens to be the participant himself.

The social network

Bitcoin’s infrastructure is built upon a network of interactions and strategies. Mining, like a competitive sport, requires individuals to rise to incredible heights to find a valid hash. This competition fosters a unique social environment where miners communicate, collaborate, and sometimes collide in pursuing Bitcoin rewards. At scale, it looks a lot like an emergent graph of a free market economy or the mycelium of a propagating fungus. Order from chaos!

We have often called this a small world network or a mandala.

The scarcity of Bitcoin, a deliberate design choice, adds another layer to this game. It creates a sense of urgency and a race for acquisition, reminiscent of limited-resource scenarios in strategic board games. This scarcity not only fuels competition but also necessitates cooperation, as seen in the formation of mining pools, where individuals combine their computational resources to increase their chances of earning Bitcoin, sharing the rewards proportionally. This is all purposeful…

…and it is my biggest gripe with Satoshi. I do not often shake my head at a design choice in Bitcoin, but I have often thought the block reward subsidy period was far too long and placed too much wealth in the hands of people who were simply able to figure out the game earliest—creating a gold rush and inordinate power in the hands of a certain few. But again, the chaos and the imperfection are also part of the design, and if I am to believe it is good, then [sigh] it is what it is. The criticism is my ego talking. It is my desire to make Bitcoin a little more perfect in my own image. Therefore, I must default back to thinking first: “Maybe there’s something I am misunderstanding about the game theory, and maybe I would agree with Satoshi if it was clarified.”

I wish more people thought this way about Bitcoin.

Human cooperation and competition

The dynamics of cooperation and competition in Bitcoin’s network are complex and multifaceted. On one hand, miners collaborate within pools to solve blocks more efficiently, demonstrating a collective effort. On the other hand, the market itself is a battleground of strategies, with traders and investors constantly competing for profit. Some day, the dynamic of Bitcoin in the real economy and competing for settlement, cash, and token liquidity will also play into the game.

These dynamics are not merely financial transactions; they represent a microcosm of human interaction and strategic play. For instance, the decision to hold, deploy, mint, develop upon, or sell Bitcoin during various market fluctuations is akin to strategic moves in a game, where players must assess risk, predict opponents’ moves, and plan their strategy accordingly.

But then there are also players in the game who don’t like to play within the chaotic yet elegant rules of the game. Instead, they seek to insert their own delusions of grandeur and throw the system out of balance.

Undermining the system: BIPs and soft forks

In BTC, the concept of a Bitcoin Improvement Proposal (or a “BIP”) and the execution of soft forks represent a contentious aspect of the system’s evolution. BIPs are proposed changes to the protocol, and soft forks are a method of implementing these changes without needing consensus from the entire network. This approach, while innovative and perhaps occasionally necessary, can also be a foothold for predatory behavior, essentially deceiving legacy nodes into accepting changes that they would otherwise reject.

Soft forks, by their nature, allow a subset of the network to impose changes on the entire system, therefore arguably resting fiduciary control in the hands of a few software developers. This shift in control undermines the decentralized enforcement traditionally upheld by nodes. The Byzantine Generals’ problem was solved by proof of work, and it has led to disastrous second-order effects. Debates over block sizes or the legitimacy of initiatives like Ordinals tokens on BTC are prime examples of the turmoil caused by such changes. At some point, I think the entirety of the greater Bitcoin ecosystem will need to come back to consensus about the proper role of the protocol, the nodes and the role of proof of work.

Or else, we all fail…

Consequences

The BTC system of implementing soft fork changes has inadvertently created a hierarchical structure within the Bitcoin economy. Armed with the technical prowess to propose and implement BIPs, developers emerge as a ruling class of intelligentsia. Concurrently, the laser-eyed “hodler” or long-term investor, often revered in parts of the economy, assumes a role akin to a priestly aristocrat. This stratification challenges the original ethos of Bitcoin as a decentralized, and it has led to confusion about a great many things.

Firstly, it leads to a concentration of decision-making power, potentially alienating a segment of the Bitcoin community who feel their voices are marginalized. This centralization of authority runs counter to any vestige of decentralization.

Secondly, the debates and divisions caused by these protocol changes have led to incredible fragmentation and brain drain within the community. Issues like the block size debate not only created technical divides but also ideological ones, as different factions advocate for varying visions of what Bitcoin is, was, or should become. Such fragmentation has slowed down the adoption process immensely, and it has created extreme confusion in the market.

Lastly, the shift towards a hierarchical structure led to a loss of trust in the Bitcoin ecosystem as a whole—which then consolidated power to people who are “trusted” because of influence or wealth. When users have perceived that a select group of developers or investors are steering the network for their own benefit, major compromises have been made to the detriment of the system as a whole.

All because we fail to let nodes be nodes and for the protocol to be set in stone with its beautiful imperfections.

The backlash to this has been the rise of Dr. Craig Wright, his desire for courts to intervene in parts of consensus, and for legal bodies to be set up to steward the protocol’s ossification.

It is unclear if these things would have happened if the developer hierarchy had not risen to their de jure places of power.

Balancing human participation and technological evolution

The path forward for Bitcoin requires a delicate balance. It involves ensuring that technological advancements and modifications to the software or networks do not erode the nature that defines Bitcoin as hard money. This balance is not just a technical challenge but a social one, requiring continuous dialogue and consensus-building with a humble understanding of the law, the history of money, and a deep respect for property rights.

As Bitcoin continues to evolve, it is imperative that we reflect on its initial vision—an open financial system where each participant has an equal opportunity to be a user and even to attempt to compete for blocks by cooperating with other people. But we also need to know when “social consensus” is detrimental or has negative, second-order consequences.

This is the real challenge. How do we admire Bitcoin’s beauty, participate in its function, and also respect its boundaries? Frankly, I do not know the whole answer myself.

I compare it to admiring someone’s custom-built hot rod car. It might not be the way I would have built it, but I admire the love and attention to detail that went into it. But since Bitcoin is a global, hard money system that cannot be changed at the protocol level, we accept it as is, or we leave it—I think.

In closing, we continue to grapple with these ideas. While it is tempting to focus on the future goal of “hyperbitcoinization,” we need to realize that one of the major goals of Bitcoin, like any economy, is to be experienced. The gold rush of mining, the struggle of validating big blocks, the tug and pull between token protocols and personalities… That’s part of the beauty of the game, too.

The beauty is in competing to create value, outsmart your foes, form businesses, and ultimately create the human element to Bitcoin’s constant ticking timechain. It is what Satoshi wanted—I think.

Watch Bitcoin15: Bitcoin’s Birthday and the future of scaling on Bitcoin

02-24-2026

02-24-2026