| Getting your Trinity Audio player ready... |

“Bitcoin cannot ever be adopted by institutional investors until the system is able to be recovered under a legal court order.”

This recent statement by Dr. Wright is a truism to anyone who understands the legal concepts of property and the concerns of legitimate institutional investors when considering the status of digital assets.

It was somewhat predictable, then, that the Ripple/XRP crowd took it as a personal attack. One of these people was David Schwartz, Ripple’s CTO:

This is so dumb for so many reasons. Why are "institutional investors" the target market for peer-to-peer digital cash? And which jurisidictions should have their court orders respected? https://t.co/HGixvyfO4H

— David "JoelKatz" Schwartz (@JoelKatz) December 24, 2022

For the last time: law applies to digital assets whether you want it to or not

First thing’s first: Schwartz’s response betrays the same fundamental misunderstanding of the law shared by most of the people who balk at the idea that Bitcoin—like any other form of property—can be seized and recovered via the legal system. He poses the question, “which jurisdictions should have their court orders respected” as though this issue is unique to digital assets: it isn’t.

In fact, the issue of competing and irreconcilable judgments has been argued over, answered, and answered again in courtrooms spanning many jurisdictions for as long as the concept of jurisdictions has existed. Two courts of different jurisdictions may theoretically arrive at different and irreconcilable conclusions over the ownership of the same property or the liability for the same actions. The approach varies from jurisdiction to jurisdiction and from context to context: for example, within the European Union, the risk of irreconcilable judgments is factored into a court’s decision on whether or not to accept jurisdiction over a given case (coincidentally, Dr. Wright was party to a precedent-setting case in the U.K. Court of Appeal where this very question was at the heart of the proceedings). In common law countries, bodies of precedent have been developed to cater to specific circumstances in addition to what may be proscribed in the statute. In Australia, for example, “the recognition of foreign judgments is governed by a mix of common law and legislation.”

International agreements, such as the 1958 New York Convention on the Recognition and Enforcement of Foreign Arbitral Awards, often form the basis for domestic approaches to foreign judgments and often place emphasis on reciprocity (i.e., we will recognize your judgments if you recognize ours).

Amidst all of that nuanced legal debate about how to approach legal conflicts across jurisdictions, not one lawyer or jurist could have credibly argued that the answer was for domestic courts to abandon their role in administering the law entirely. Implicit in Schwartz’s challenge, posed as a question though it may be, is the assertion that the courts will or should do exactly that.

Which brings us to XRP…

Dr. Wright’s response to Schwartz’s challenge inevitably led to an assessment of Ripple’s beleaguered XRP project, something Schwartz seems quite keen to avoid:

Craig made a dumb argument. I pointed out that the argument was dumb and did not attack Craig at all. He responded by attacking me and XRP.

Craig is deliberately trying to be painful to engage with to prevent his ideas from being criticized publicly. You can see for yourself: https://t.co/WmwUS6uKqq pic.twitter.com/mioe8Kzog5

— David "JoelKatz" Schwartz (@JoelKatz) January 2, 2023

It’s all too fitting that Schwartz would fail to see the connection between Dr. Wright’s point about institutional adoption and the criticisms he went on to aim at XRP: namely that it is a useless system, the only contribution of which has been to the pockets of its founders. It’s this very lack of utility that makes XRP such an obvious case of an illegal, unregistered securities offering: hence why the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) took action against the project on that very basis.

On some level, that’s the only reason Schwartz waded into this argument in the first place. He has to argue that XRP has practical use (and is, in fact, being used) because any other position is an admission that the SEC is barking up the right tree. That’s because if XRP was being offered to investors who did so on the expectation that its value would go up based on the future development of XRP and the Ripple network (as opposed to any present utility), then it clearly amounts to an unregistered (and illegal) securities offering.

“Unlike ordinary assets such as groceries, XRP is nothing but computer code represented on an electronic ledger. It has no historical existence and no intrinsic value absent a market for its transfer,” the SEC argued before the court in December.

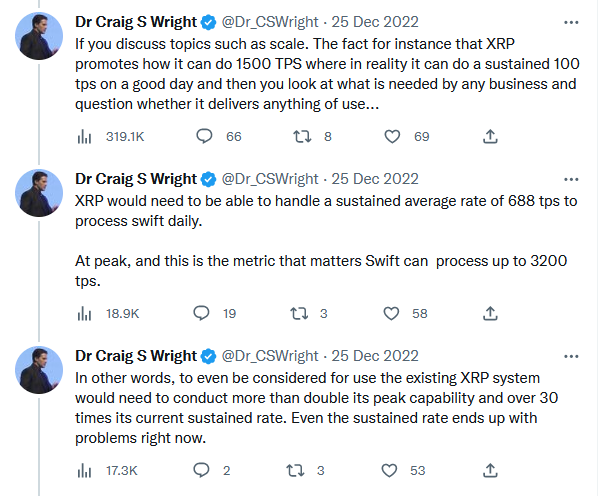

That’s also why Dr. Wright barbs Schwartz on the topic of scaling.

Source: Dr. Craig Wright’s Twitter

XRP cannot and does not scale, which means that as far as utility is concerned, the project was dead on arrival. The empty promises by executives that such utility would be created at a future date serves only to prove the SEC’s case: that those purchasing XRP did so on the expectation that some future efforts by Ripple would create such utility.

That’s also presumably why Schwarz got so prickly when the subject of institutional investors came up in the first place. What better evidence of a compliant and useful system than institutional adoption? Indeed, Ripple’s filings in the SEC’s case against it repeatedly make reference to financial institutions which it alleges use Ripple’s products.

No – more equivocation from ripple

The claim is one that has been made over eight years now by this company.

They claim banks are using their product. Yet, not a single case can be demonstrated. If you are saying that you have a solution and that it is being used in production https://t.co/4pYnXN19bB

— Dr Craig S Wright (@Dr_CSWright) January 4, 2023

In response, Dr. Wright raised the Sarbanes-Oxley Act. The Sarbanes-Oxlely Act was put in place in the wake of scandals like Enron, and obliges public companies to adhere to strict financial auditing requirements. The thrust of the rules is to protect investors from fraudulent financial reporting by public companies.

Ripple is not a public company, so the Sarbanes-Oxley requirements don’t apply to them directly. They will, however, apply to these ‘institutional’ partners that Schwartz desperately needs people to believe they have. Which means if Ripple is indeed partnering with these institutions, there must be some trace of it in the latter’s legally mandated disclosures.

The best demonstration of this comes from Schwartz himself. In an effort to refute Dr. Wright, he cited a puff-piece Youtube video ostensibly spliced together by Ripple’s marketing team: in it, a Santander executive explains how the bank’s payment app runs on Ripple. But beyond this marketing, there’s no evidence that Santander (or any other institutional investor) is using XRP, as you’d expect from an entity obliged to follow SOX and Dodd-Frank rules.

Again, Dr. Wright is entirely correct on this point: internal communications between Ripple executives secured by the SEC confirm that such puffery was a deliberate strategy to fuel speculative XRP trading. They show Ripple employees discussing plans with then-CEO Brad Garlinghouse to drive speculative trading volume, including by announcing business deals in a manner that would “spark speculation about potential partnerships.”

The SEC complaint against Ripple itself spells out a practice of subsidizing companies to use Ripple products in order to generate XRP activity that it could point to as evidence that it has any utility at all.

Schwartz also made a pitiful attempt to pretend that the SEC’s statement that ‘the banks and financial institutions that Ripple refers to as its customers did not use ODL (Ripple’s on-demand liquidity service facilitating cross-border transfers into local currency)‘ amounted to an implicit assertion that they use XRP in other ways. For that to make sense, you’d have to look past the enormous and obviously deliberate qualifier in the SEC’s wording which shows they are merely quoting Ripple’s assertions as opposed to making any themselves. Even still, Schwartz conveniently ignores the rest of that very filing, in which the SEC states that of the ‘hundreds of customers’ that Ripple claims are using Ripple products generally, most of them use xVia and xCurrent, two messaging services that plainly do not use XRP.

He also leaves out the SEC’s argument from further down: that Ripple artificially manufactured ODL usage by paying companies to use it in the hopes that it would generate more activity in XRP generally. Why was such an illusion necessary if, as Schwartz claims, financial institutions and other customers were already using XRP in any meaningful way?

If it looks like a security, walks like a security, and talks like a security, then it’s a security

Since so much of the conversation around Ripple’s dire situation with the SEC gets derailed by desperate XRP holders and those whose own pump-and-dump schemes depend on the SEC’s case failing, it bears repeating: Ripple sold $1.38 billion worth of XRP to investors, and Ripple’s most senior executives pocketed $600 million of it, according to the SEC.

Because Ripple’s founders failed to register this as a securities offering, they did not comply with any of the disclosure requirements mandated by the U.S.’ securities regime. As a result, not only did XRP purchasers not have access to the same kind of detailed documentation that the SEC argues they were legally entitled to, what information they did have access to was limited to whatever marketing puffery that Ripple executives saw fit to share.

And while Ripple now cries foul that the SEC didn’t do their due diligence for them and forewarn that the unregistered offering of XRP was highly illegal, according to the SEC’s complaint Ripple sought—and ignored—independent legal advice, which told them that their plan may amount to an illegal securities offering.

And it was a securities offering. The U.S. securities statute defines a number of securities: the most applicable in these cases is that of an ‘investment contract.’ Whether something amounts to an ‘investment contract’ and, consequently, a security is determined by the Howey test. Originally set out by the Supreme Court in 1946, Howey holds that an investment contract will exist where:

- There has been an investment of money

- Into a common enterprise

- The investment is made with a reasonable expectation of profit reliant on the efforts of others

The first two prongs are typically uncontroversial and in the cases of digital asset offerings, are almost always met. Even LBRY accepted this, challenging the SEC’s case against them only on the third prong of the test. Yet Ripple has thrown everything—including the kitchen sink—at the SEC’s case, improbably arguing that their XRP offering did not involve an investment of money, nor was it made into a common enterprise.

They point to the existence of some XRP that were distributed to select individuals for free to refute the first prong, a junk argument which can be easily dismissed in light of the vast majority of XRP which were issued in exchange for money.

In relation to the second prong, XRP provides a similarly deficient argument: they argue that XRP is not the equivalent of stock, and thus there has been no investment into a common enterprise. This ignores that the Securities Act defines an ‘investment contract’ separately from ‘stock’ as type of securities, and it is under the former definition that the SEC brings its case against XRP.

The third and most contentious prong can itself be split into two questions: first, was there a reasonable expectation of profits, and second, was that expectation reliant on the efforts of others.

It is here that Dr. Wright’s arguments to Schwartz are particularly relevant. XRP had no use from it since it was first issued, and statements from Ripple founders at the time make clear that they would be investing considerable time and the money raised by XRP sales to search for some use case which could create value for the token and its holders.

For example, while Christian Larsen and Brad Garlinghouse (former and current Ripple CEO, respectively) were dumping their own XRP on the market, Garlinghouse was assuring the Ripple fanbase that he was ‘very long’ XRP. At Ripple’s own conference, he trotted out one of the favorite lines of the crypto scammer: that he is not focused on the price of XRP in the short term but over the long term, and that he had ‘no qualms saying definitively if we continue to drive the success we’re driving, we’re going to drive a massive amount of demand for XRP because we’re solving a multi-trillion dollar problem.’

It has failed to find any such use case, as Dr. Wright pointed out, but that doesn’t need to matter to the Howey evaluation: purchasers of XRP did so with the expectation of profits arising from the increase in XRP’s value as a result of Ripple’s efforts to find use-cases for the token and develop the market for it.

The record is replete with statements made by Ripple execs to various media outlets in which they confirm that utility is ostensibly what Ripple is aiming for rather than what it offered at the time of sale.

Garlinghouse told Bloomberg in 2018 that the reason XRP had done so well was not because it was enjoying any utility but on the expectation that some future value would be created by Ripple’s continued work on the project:

“[W]e have found that part of the reason why XRP has performed well is because people realize. . . if we work with the system to solve this problem and we can solve that problem at scale, a problem measured in the trillions of dollars, then there is a lot of opportunity to create value in XRP.”

If that doesn’t sound like an investment contract, what does?

Law is law

If you hear someone try to argue that some perceived ambiguity in the law should prevent its application, they either don’t understand the law or are trying to make sure that you don’t. There is no such thing as ‘outside the law,’ no such thing as ‘the law doesn’t apply here.’ In rare cases where there is genuine ambiguity, the law is generally good at dealing with it. After all, legal systems around the world have centuries of experience in dealing with ambiguity: in that respect, digital assets or ‘crypto’ are nothing new.

That doesn’t stop the Schwartz’s and Ripples of the world from trying to pretend otherwise, of course. Like Ripple and the legal advice it pretended it never received, Schwartz can bury his head in the sand and pretend the law doesn’t apply all he wants. Also like Ripple, Schwartz is in for a rude awakening.

Follow CoinGeek’s Crypto Crime Cartel series, which delves into the stream of groups—from BitMEX to Binance, Bitcoin.com, Blockstream, ShapeShift, Coinbase, Ripple,

Ethereum, FTX and Tether—who have co-opted the digital asset revolution and turned the industry into a minefield for naïve (and even experienced) players in the market.

New to blockchain? Check out CoinGeek’s Blockchain for Beginners section, the ultimate resource guide to learn more about blockchain technology.