|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

Meet the new boss! Same as the old boss!

Wait, who?

Ok, this editorial will be about a British venture, but not a band, and not the Who. Instead, it’s a history lesson going back a few hundred years.

Investment schemes have been around for a very long time. In all likelihood, the first pyramid schemes are lost to time after being run by opportunists whose names we will never know. Modern investment fraud goes back into the 1800s, and fractional reserve bank runs go back to at least the 1600s. Charles Ponzi popularized them so much, that they even named a specific method after him!

We also have ample evidence of a general distrust for predatory exchange rates and bankers given to us by the Apostles Matthew and John who describe the Son of God making a whip to drive the money changers out of the temple.

Source: Carl Bloch (1834-1890), “The Cleansing of the Temple” (photo: Public Domain)

But are there lessons to learn from the history of investment fraud and speculative bubbles, or should we even bother because “Bitcoin fixes this?”

Tulips. So many tulips…

Let’s focus on mania and bubbles. People often cite Tulip Mania as an example of an investment frenzy that destroyed lives, but there’s some evidence that this particular bubble didn’t really happen the way some would like us to believe, and I think there’s a better bubble to learn from for today’s shrewd Bitcoin investor.

It began when a British company was founded in 1711 by an act of the Parliament—creating a very trustworthy public/private entity as a means to reducing the British national debt that had been created by a trade imbalance from the sudden emergence of the Americas as a factor in British economics. The government enacted a monopoly over various goods and called the entity “The Governor and Company of the merchants of Great Britain, trading to the South Seas and other parts of America, and for the encouragement of the Fishery.” Rolls off the tongue, huh?

For short, it was called “The South Sea Company.”

Catchy logo, killer devs, and an awesome community of whales – I mean, whalers.

Since the 1500s, the slave trade was an immensely profitable corner of the British economy, and public confidence in the industry was at an all-time high in the early 1700s. Everyone in the empire had missed opportunities to invest in the industry because it was one of those “up only” sectors for over a generation, and average citizens expected the industry to grow forever. And if slaving wasn’t going to be great, whaling certainly would! But, of course, that isn’t what happened…

The South Sea Company began by offering Celsius HODLers—whoops! I’m sorry, I mean company stock owners—6% interest paid out on regular intervals just for being part of the South Sea “community.” Unfortunately, treaties with Spain only allowed Britain a limited amount of trade and granted the Spanish a percentage of the profits that wasn’t initially planned for. Spain also levied new taxes on slaves and almost completely stopped British ships from being able to import other goods and services altogether. Already, The South Sea Company was in trouble…

Over the next few years, the company bled money because it wasn’t actually doing much of anything valuable, but the stock price continued to pump on the notion that it should pump because it was the market leader in such a booming new sector. Amid some early sings of financial weakness, Sam Bankman-Fried—I mean, King George—ended up stepping in to buy a majority of the company which added a de facto stamp of approval to its financial health, and things stayed on track pumping valuations.

“WAGMI, Fam! Anything for muh community.” – King George I, 1720. Probably…

The company even ended up buying up a large portion of the national debt for pennies on the dollar, and it was essentially wash-trading South Sea Company stock against its debt position as a primary way to earn real money for a time. It was a wild speculative bubble for a company that had almost no real revenue relative to its overall valuation.

Bring in the influencers!

The 1700s were a time of great flux for the British Empire. Wealth was transitioning from being a function of land and title and moving toward entrepreneurship and the utilization of modern financial instruments. This brought in an era of influencers! Stock promoters would stand on the streets and hustle the passersby.

This the 1720’s version of Laser Liotta accounts on Twitter. (Source: Wikimedia)

The greatest scientist and one of the most respected entrepreneurs of the era was one of the leaders in this transitional period of finance. Michael Saylor—I mean Isaac Newton! Newton was an early critic of Bitcoin—I mean the South Sea Company, but he was happy to be a 1%er of his era while holding very little real estate and instead focusing on stock and other modern stores of value! Happy to write it off, Newton sold his South Sea Company stock he had acquired early and moved on with his life for a time. He seemed happy to have made some money, but wasn’t anything like the investment hounds of the era.

Sound familiar?

#Bitcoin days are numbered. It seems like just a matter of time before it suffers the same fate as online gambling.

— Michael Saylor⚡️ (@saylor) December 19, 2013

Newton was a sophisticated investor with intimate knowledge of the market as he held positions at the National Mint and worked in official capacities for the nation and the crown. And at some point in the middle of the bubble, he looked deeply at the fundamentals of the company whose stock he sold and the market as whole, and he decided to “go all in” on South Sea stock near the top of the market

This was a massive signal to the people of England to follow his lead. How could such a genius be wrong about such an investment in such a big brand in the middle of such a lucrative industry during such a momentous era of economic transition? Right? RIGHT?!

“There is no second best publicly owned slaving and whaling company.” -Isaac Newton. Probably

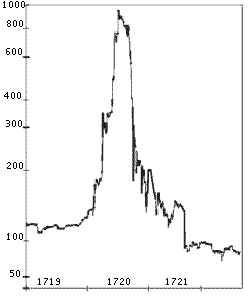

Ultimately, the stock went from £100 to £1,000 and then right back again inside of a year. The bubble burst, the investors got “rekt,” and the people of the English-speaking world learned an important lesson about investing in an appreciating stock with powerful influencers, lots of circumstantial fundamentals but no real value creation for the real world.

South Sea looks like a shitcoin, huh? Source: Wikimedia

What did we learn?

Well, some of us learned that an asset which appreciates in price due to popularity and speculation but with diminished, diminishing or non-existent underlying utility is a bad investment opportunity. We also learned that just because something was a good trade doesn’t make it a good investment. Most importantly, we learned that financial instruments can be powerful when used for good, but they also have lots of risk for unsophisticated investors—and sometimes sophisticated ones too.

Just because something is “performing” doesn’t make it valuable—no matter how many people think it is. This story played out many times too. The main lesson is about the speculative nature of things like BTC and Ethereum, and why we should have the patience and foresight to take a step back when things get unreasonably hot in the market.

Be good to each other!

Recommended for you

The views expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the position of CoinGeek.

03-06-2026

03-06-2026