|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

https://youtu.be/z07TPyXw2OE

In recent years, a hot topic surrounding Bitcoin and proof-of-work mining have been their energy efficiency and the environmental impacts they generate.

On day three of the BSV Global Blockchain Convention, a panel moderated by CoinGeek’s Patrick Thompson, including TAAL CEO Richard Baker, Alex DeVries from Digiconomist, Prof. Robert Lee from 518 Blockchain Community, and Kurt Wuckert Jr. from GorillaPool, discussed blockchain mining, the amount of energy it consumes, how to make blockchains more efficient, and more.

Who are the panelists?

- Richard Baker is the CEO of TAAL Distributed Information Technologies (CSE:TAAL | FWB:9SQ1 | OTC: TAALF). It’s a leading BSV network miner and transaction processor.

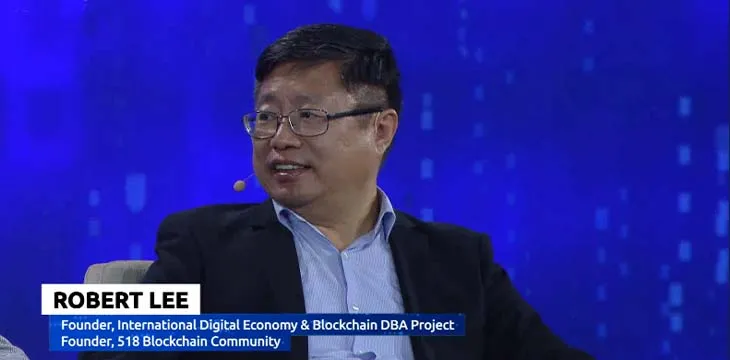

- Prof. Robert Lee is the Founder of International Digital Economy and the Blockchain DBA Project. He also founded the 518 Blockchain Community.

- Kurt Wuckert Jr. co-founded GorillaPool, a distributed BSV mining pool. He’s proud to say that GorillaPool has mined the most energy-efficient blocks in Bitcoin’s history.

- Alex DeVries is the Founder of Digiconomist and the Bitcoin Energy Consumption Index creator.

How much energy does blockchain mining consume globally?

Thompson opens the discussion by asking de Vries to tell us how much energy blockchain mining consumes globally. It makes sense to ask him since he’s spent the last half a decade or more researching this both academically and independently.

“If you add all crypto assets that can be mined together, you’re probably talking at least as much as all global data centers in the world combined,” de Vries tells us.

This includes all of the data centers for Meta, Amazon, Google, and other corporate giants, as well as the legacy financial system. He tells us that this accounts for more than 1% of global electricity usage and that BTC and Ethereum are responsible for most of this usage.

Thompson asks whether this is problematic, and Richard Baker answers that it is because policymakers look at the headlines, and amidst an energy crisis like we’re in right now, they have a responsibility to decide whether industrial and household energy needs should take priority over blockchain requirements. He notes how we already see policy in the European Union and parts of the United States, which is considering a proof-of-work ban. However, he points out that not all proof-of-work blockchains are the same, and we need to make sure that policymakers understand the utility of blockchains like BSV.

Does mining provide real value, or is it negative for society?

Wuckert is up next, explaining the value created by mining blocks. He highlights the value created by the internet and notes that the same scrutiny over energy usage isn’t applied to things like AWS or other cloud computing systems. He then explains that in large (several GB) blocks, we can fit “an incredible number of transactions,” but that it’s difficult to judge the value of those transactions because they’re qualitative in nature.

Thompson then asks Professor Lee if blockchain mining has a net positive or a net negative outcome. He responds that if certain conditions are met; using green energy, delivering utility, playing by the regulations, and paying taxes, then it can be a net positive, but otherwise, it will remain a net negative. De Vries answers the same question, saying that “it depends.” He notes that there’s still a debate around whether proof-of-work is the only way to do things like peer-to-peer transactions. Even if proof-of-work is the only way, he says it becomes hard to justify eliminating the need for a trusted third party if the latter is more energy efficient.

Wuckert carries on from this question to explain the differences between proof-of-work and proof-of-stake. He notes that in POS systems, whoever holds the largest number of coins is king and that over time, their power over the network only continues to grow. By contrast, in proof-of-work, inefficient and malicious actors are pushed out, and the nodes that produce the most value flourish.

Miners on the move and how to improve efficiency

Thompson notes that with several high-profile crackdowns on mining in recent times, many miners are on the move. He asks Baker to tell him where most mining is occurring today, and he explains that it’s shifting towards North America. “We’ve seen $4.5 billion worth of hardware shipped into North America to power BTC this year,” Baker tells us. However, he reminds us that not all states are miner-friendly, with New York being a good example of a state that’s hostile towards blockchain miners.

Professor Lee elaborates on how miners can become more efficient to not draw the same ire from governments. He counts finding clean, renewable energy sources, using modern, efficient mining machines, and improving the efficiency of mining itself (e.g., by reducing cost per transaction) as ways to improve things.

Baker seconds Lee’s points, saying that miners will be subject to ESG regulations. He points out that the BSV network is becoming super-efficient with growing block sizes.

Wuckert draws attention to miners using excess energy such as gas flares in oil and gas fields as one way to use energy that would otherwise have been wasted. He also says that many miners use the heat from mining for other useful things, such as heating greenhouses.

Staying on the subject of renewable energy for mining, de Vries points out that the use of renewables has actually gone backward, at least on the BTC network. After the mass exodus of miners from China, many relocated to places like Kazakhstan, where energy is still mostly coal-powered. He says he doesn’t know if that’s also true for BSV as he has never examined it.

Is a ban on proof-of-work an effective solution?

Thompson then poses whether a ban on proof-of-work would solve the problems many politicians deem it to have? De Vries answers that there is no perfect solution and that miners will simply move to other jurisdictions. He reiterates that when China banned it, the carbon footprint went up, opposite the intended consequence.

Wuckert follows this by pointing out that when one jurisdiction bans something, it creates an opportunity elsewhere. He points out that the ban in China created opportunities in North America, and if New York bans it, it will create opportunities in Texas. This regulatory arbitrage will always be a factor, so bans are largely ineffective in the grand scheme of things.

Watch the BSV Global Blockchain Convention Dubai 2022 Day 1 here:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ggbZ8YedpBE

Watch the BSV Global Blockchain Convention Dubai 2022 Day 2 here:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RzJsCRb6zt8

Watch the BSV Global Blockchain Convention Dubai 2022 Day 3 here:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RzSCrXf1Ywc

08-17-2025

08-17-2025