|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

Space data storage: hack-proof, apocalypse-proof, and government pressure-proof.

Throw data into space?

Of course, the future of practically everything is in space. But we’re going to delve into something that’s not so distant in the future. In a few years from now, some of our data will be stored in space.

Every week, we have to weed through numerous emails, mostly for PR and some invites to events. I came across something that immediately caught my eye—an invite to a webinar about data centers in space. I tried attending the webinar but it’s rainy season where I am, and internet service here is apparently not “water-proof” and I got disconnected. So instead, I reached out to SpaceBelt to know more, and ended up speaking with CEO Cliff Beek in what turned out to be quite an entertaining and educational conversation. Luckily, my internet connection cooperated with us that day.

SpaceBelt, a global satellite network for securing highly sensitive data in space, aims to build the information ultra-highway and eradicate hacking threats by taking data storage up into a terrain completely untested by today’s hackers.

“Imagine how organizations would operate if data vulnerability was no longer a focus of day to day operations. A world free of insecure data and jurisdictional hazards. A global data storage network based in space,” it says on their website.

But how does this work exactly?

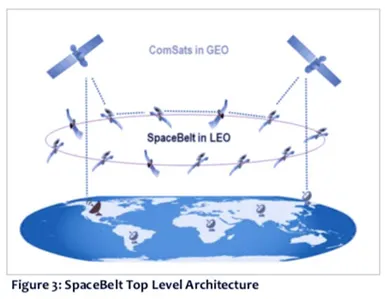

“So we’re putting into space between eight to 12 low earth orbit satellites or LEOs. And we’re going to be interconnected between those LEOs with laser optical communication layers, moving data about a 10-gig wave,” Cliff says.

“We’re located at the equatorial plane. So it’s about 800 kilometers above the earth at the equatorial plane, moving around the globe very quickly but interconnected into this “constellation” of satellites where we have eight petabytes of data storage,” he explains.

“So our model is really to take customers’ information that need to be highly secure and move it around the world in a very secure fashion.”

Why the equator?

If the LEOs are hanging around at the equatorial plane, then that means we’d probably see it in the Philippines—probably think it’s some UFO or something, I asked Cliff.

“Yes. And we chose the equatorial plane because of the Philippines because that’s our central market,” he joked. Cliff, I found out, has been running a company called Star Asia Technologies, which has been in operations for about 10 years, in Manila where I live. He even spent quite some time at the university I attended, where I also briefly worked as a lecturer.

“I have an affiliation and an orientation towards the Philippines. I have an office there so I really enjoyed being there,” he said. “But joking aside, the equatorial plane is because what differentiates our project from any other project in the world—I mean this is one thing that made us really unique and different—is that our communication antennas are not facing the Earth.”

This baffled me a bit. Luckily, he immediately explained further, and it’s apparently a very clever solution.

“When you look at, say Agila I and II—the satellites from PLDT that were purchased by Asia Broadcast Satellite—those satellite reflectors are all facing down into the Philippines. And you need regulatory approvals to operate in the Philippines or any other country that you operate in.

So when we started planning for a LEO constellation, we were thinking about how we could be smart about it. And it’s called our regulatory pact, if you will. We turned our reflectors up so we’re flying underneath the existing geostationary satellites—and all of those are positioned at the equatorial plane at about 22,000 miles above the Earth. We’re flying underneath them with our reflectors facing up so we’re using them like a cell tower so we don’t have to get landing licences in all these countries because the existing operators already have it.

It was a real breakthrough for us from a regulatory perspective and it made life easier for us that were not filing for all the regulatory filings and we’re not having to get license in every country want to do business with. So you know that was the reason that we’re at the equatorial plane because all the geostationary operators are in that same plane but at 22,000 miles above the earth we’re at about 700-800 kilometers so we’re using them to balance our signals up and down.”

To get a better visual of what that looks like, here is a diagram from SpaceBelt.

Government-proof?

So if they’re not under anybody’s jurisdiction, who has authority over regulations, standards? It’s apparently a grey area that even lawyers are trying to figure out.

“Yeah, that’s a great question and it’s one that we find that lawyers of these different large groups have been asking us,” Cliff says.

There have been some instances where governments tried to gain access to data from companies—incidents where authorities have pressured companies to comply, or they will be shut down or their operating licenses revoked. The recent case of Telegram comes to mind. So does the case of Apple being pressured by the FBI to unlock an iPhone belonging to Syed Rizwan Farook, the suspect in the mass shooting in California last year.

And as recent developments in regulation over data progress, more questions arise surrounding data privacy and rights. Joe Stanganelli, principal at Beacon Hill Law, describes what’s worrying about the EU’s recently passed General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR):

“The thing that has made GDPR so big and scary—aside from the potential for unprecedentedly massive fines—is its broad reach. Specifically, the idea that the EU has effectively promulgated its way into being the world data police,” Stanganelli wrote.

But while this may be a problem for Earth-based data centers, space-based data centers on the other hand, are an entirely different terrain—both literally and legally.

Government pressure and giving users back full rights and control over their data

“The idea of putting that into space or putting a country’s information or even their encryption keys in space creates a data sovereignty—no country can subpoena that data, and say, ‘hey we want you to turn that data over to our legal system because we anticipate that there is some kind of illegal activity,’” Cliff says.

“We’re trying to help countries and corporations comply with jurisdictional venues to allow them to operate in a sovereign environment. So who has control over it? Well, it’s a grey area.”

Cliff clarifies, however, that they are not trying to evade compliance and regulations. But they are—and I believe this is severely important in this day and age—giving data owners back full control over their data, which they rightfully deserve.

“What happens is that the country starts putting undue pressure on the server the ISP and the service provider, and saying if you don’t turn that data over to us we’re going to shut down your license to operate.” Cliff says in the case of SpaceBelt, should they receive a subpoena to give up data, it’s not a matter of decision or willingness to comply, but a matter of ultimately not having the capability to do so.

“Putting data in space enables countries and companies to better understand and manage their sovereignty rights in the world,” Cliff explains.

“It’s complex but we feel that what we’re offering to companies is not a way to avoid the jurisdictional venue, not a way to avoid jurisdiction but a way to allow them to be able to manage their data in a safe environment.”

Referring to the recent Apple vs. FBI legal tussle over the iPhone in question, Cliff explains how their system is actually giving data owners their full rights over deciding whether to turn over their data or not.

“From what I’ve heard, Apple wanted to help the government in those situations by unlocking the back door but they didn’t want to set a precedent,” Cliff says, adding that Apple ran into a similar problem in China, which threatened to shut down the technology company.

“So that’s a threat to companies trying to protect data in a regime government that’s looking to grab access to information,” Cliff adds.

“In our situation, if we were to receive a subpoena for us to get data from your information to them, we don’t have it. We don’t have a backdoor. There’s no way for us to get into the data partitions for your use. We’re just managing and authorizing access to it. The authority would have to go directly to the customer and get their encryption keys to unlock it.

So the protection that we offer is that if we were subpoenaed we don’t have any access to it. They could shut us down. They could do whatever they want. But it’s only our customer that has access to it and they’re in the best position to determine their legal fate about whether or not they’re going to turn over the data. So it protects the customer from us receiving undue pressure to turn over the information because we just don’t have the backdoor.”

Hack-proof? Out of reach of hackers—literally and figuratively

Security is one major concern for all businesses in the digital age. And it’s also SpaceBelt’s biggest value. So how is a space-based storage more secure? As I was scouring the web for information on them, one thing I saw mentioned was the fact that it is not connected to the Internet.

According to Cliff, a small dish will be set up at the client’s location, and it will communicate directly to the satellite above and be able to move that data without having to be connected to any ISP. He explains this using a hypothetical data transmission from a bank in the Philippines to New York.

“Rather than going through the Internet service provider (ISP), you would go directly up into the orbit, into space and you would connect to the LEO constellation that has a platform that moves your data around to New York and directly down to the location where you want it to go. So instead of going out through Smart or PLDT’s (ISP’s in the Philippines) Internet service providers, you’re essentially going straight up. You’re avoiding that (internet connection). You’re bypassing all of that—the ISP’s in the region and you’re not connected. You’re completely detached from the fiber optic services from the ISP’s. Think of it as just having a dish on the roof of your building. You would not be going out through a fiber connection, you’d be going directly up and bypassing, and not being connected at all to the public Internet.”

As for the hack-proof aspect, Cliff says hacking a satellite-based storage is an entirely different arena—one that today’s hackers do not have any experience or skills in. In fact, he says their best bet at taking the satellites down is to shoot them.

“The skill set to get into a satellite and redirecting satellite signals is a challenge for the average hacker. Not to say that somebody couldn’t start trying to jam the network or do something that’s much more sophisticated. But for today’s hacker, the skill set is much different. And we don’t want to put a challenge out to hackers and say our system’s hack-proof but it’s very difficult to hack into a secured storage provider at eight hundred kilometers above the earth. It’s a different skill set and I don’t think anyone today—unless you are going to launch a missile trying to shoot down one of these LEOs—is going to be able to do it.”

Cryptocurrency exchanges are begging for the service

If space data storage really is much more secure than Earth-based storage, I’m pretty sure cryptocurrency exchanges would be interested. Based on the influx of cryptocurrency companies giving notice to SpaceBelt, I was right. Before they can even launch, the demand for the service is already overwhelming—and they’ve noticed that they’ve been gaining a lot of attention particularly from the cryptocurrency industry.

Space data storage can give cryptocurrency wallets and exchanges the security they need, particularly for cold wallet storage. Just for the first quarter of this year, $670 million has been lost to cryptocurrency hacks. Adding the other hacks from the years before that will probably hike up the total to billions of dollars. The hype and deluge of investments pouring into the industry will undoubtedly attract more malicious intentions. Unsurprisingly, SpaceBelt instantly got a lot of attention from cryptocurrency companies—around 80% of their inbound inquiries.

“Our very first customer that came in when we announced our project was a company called SolarCoin. They wanted to protect their vault in low Earth orbit because of the hacks that were occurring at most of the exchanges. And I would say that 80 percent of the inbound inquiries we get are from crypto currency block chain companies.

We did a white paper in early February with IBM. They were interested in putting blockchain in space to have this global distribution of security. From that publication we started getting massive amounts of requests from various digital currencies. And we’ve signed a couple of memorandums of agreement. They wanted to be able to eliminate the volatility of their cryptocurrency because of the threat of being hacked,” Cliff says.

So could this be the future for cold wallets, and the next step to making cryptocurrency exchanges and wallets more secure?

“Yes, absolutely. And it’s been it’s been really interesting for us we don’t really know. We’re not interested in issuing any coins or anything like space coin or anything like that. But we see a lot of these exchanges looking to put their currencies in space as a protection against hackers.

So we’re still two years away from fully completing our network. But these companies are looking to find solutions to put their exchange in space.”

Apocalypse-proof: is space storage the ultimate time capsule?

If there were some form of apocalyptic/semi-apocalyptic occurrence on Earth, does that mean the data in SpaceBelt’s “cloud constellation” would be the last thing that survives? Aliens would probably have a look at it—if they ever come around and see nothing but rubble on land.

“This is kind of funny you said that,” Cliff says. Apparently, I’m not the only one to think of doing the same thing with SpaceBelt. He compared it to Elon Musk including Isaac Asimov’s “The Foundation Trilogy” in the payload of SpaceX’s Falcon Heavy, along with Starman the dummy in a Tesla Roadster. The concept of putting something of historical significance as an artifact to be protected—there is a non-profit org looking to do that on SpaceBelt.

“Somebody contacted us and said, ‘would you guys be willing to offer us maybe a full terabyte of data storage for us to put something in space?’ And as an advertising media thing we agreed to it,” Cliff narrated.

“We’re doing it.”

He points out, however, that there are conditions to the surviving data being accessible to survivors—if there were any.

“The problem would be if all the Earth’s settlements were destroyed, then we would have a hard time accessing the data inside the spacecraft. But this could be an interesting one—actually, the application for a company that’s looking to store something that’s critical to them needs to be off the ground in the event that there is some kind of catastrophic event on the ground. And more importantly, be able to move it from point to point.”

Further scaling

Ah, scaling. One of the biggest questions for all businesses, traditional and blockchain-based. SpaceBelt is two years away from launch yet they’re already getting bombarded with calls for far more than what they initially planned for.

“Our storage capacity is really not as large as a data center. We’re putting in space about eight terabytes of storage capacity. And we’re really aiming at customers who need to protect very highly sensitive, very small amount of data such as transactional data from a bank, for example. And so customers in our target markets are usually financial institutions or government agencies that are trying to securely protect data and move it globally. So this data highway component is really to get completely detached from the terrestrial networks,” he says.

So do they have plans to scale up to accommodate the many applications that could benefit from this? Healthcare data alone is expected to literally “shoot to the Moon,” well to a third of the way to the Moon if stacked in tablets by 2020. While excitement for the project is high, most of us will have to wait a bit.

“Yes, we do (have plans to scale up). Our system is modular—you can add additional LEOs to the Constellation and we anticipate adding memory satellites to our constellation as our market grows.

And what’s become more interesting for us is when we first started thinking about how much capacity is in space and what we would need, and we became overwhelmed while we did. We’re going to need to add quite a bit.”

And since it would not be practical to shoot so many satellites up into orbit, Cliff says they have been devising a more practical, less outer space-consuming (pun intended) scaling solution.

“What was interesting is that as customers started coming to us with data protection concerns, we started getting these ideas that the data could be residing on the ground. But the data keys or the encryption keys can be stored in space. And this started to evolve to more conversations that we’ve had with blockchain and cryptocurrency concerns—where they were more concerned about access to their vaults.

You don’t need to store all the data in space but if you just store the encryption keys and you allow that very highly secure access authorization to those keys, you would pretty much solve the problem of having large amounts of data on your satellites. The data can be stored in various geographic locations but the keys themselves were important.

It really became more interesting for us in terms of encryption key as a management space. But to answer your question directly: we do anticipate adding more LEO capacity to the Constellation as the market demand picks up.”

What about the Space junk?

Cliff says SpaceBelt does not anticipate becoming a contributor to space debris since the satellites can be de-orbited and it will burn upon re-entry into the Earth’s atmosphere.

“The good thing about lower orbit satellites is, after the economic life of these satellites—which is about ten years—when you retire and de-orbit one of your LEOs, there is enough fuel in it to take it out of the orbit and let it drift. It then comes into the atmosphere and it essentially burns up on re-entry.”

So…uhm, what’s the dollar figure?

Cliff says comparing their costs to current standards would have to cover two major expenses: storage and connectivity. And that surprisingly, their system has competitive advantage over current market costs.

“Most companies that we’ve seen from the financial institutions are paying about $30,000 per one million cyber security insurance against hackers and our cost is way below that. So companies that are looking to put highly sensitive data in space—information that absolutely has to be protected—this is at a point like it’s about $5,000 per month for three terabytes of data storage and that particular access point is from anywhere in the world.

In that price you get international global transport. So you’re not paying for connectivity. You’re essentially getting a global transport and data storage.”

Solar flares and other cosmic elements

I asked Cliff how “safe” the satellites are—they are, after all, carrying data that should survive even if everything on the ground goes haywire. He commended me for the question, and explained how SpaceBelt’s “space-hardened executives” have fully prepared for all these risks.

“That’s a very insightful question, Cecille. I’m very proud of you for that question,” Cliff says, “because it is the biggest concern of any satellite organization, flying anything in space—is the access to radiation and how to mitigate against it. So we chose the equatorial plane not only for the locations of the geostationary satellites. But in Leo—in low earth orbit and at the equatorial plane, the interference and the likelihood of high intensity radiation or any kind of flare up is very low.”

“It’s a very friendly neighborhood,” Cliff asserts. “So for that regard just the location of where we are is good and favourable. And the second thing is that the group—our engineers and designers are space-hardened executives. In other words they’ve flown in and they’ve developed lots of different satellites. And what we’ve created in our memory systems is highly protected components.

So these are what they call space-hardened and they have 3 to 1 backup in the event that there’s an issue with any kind of memory loss. But the components are highly shielded and they’re put into highly protected environment. Now, one of the examples we like to use when someone says, ‘who’s doing this today, what’s an example?’ The International Space Station (ISS)—which hosts lots of astronauts and many computers in space. Their components—there’s lots of silicon, lots of memory, and lots of computing going on at the International Space Station. And it’s something that we have demonstrated that it’s already in existence. So by putting more of it into space backing it up and protecting it, we feel that in the event that there is any kind of a direct radiation hit, we have plenty of capacity and backup. But the components are what we call space hardened and tested and flight tested before they even go up.”

Cecille de Jesus

@the_scientress

07-06-2025

07-06-2025