|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

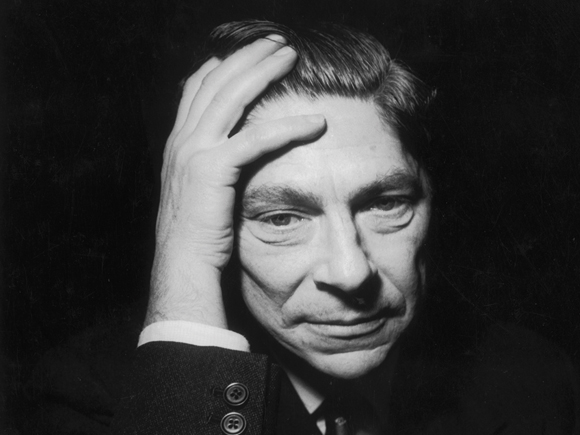

“On Tuesday, March 1, 1983, Arthur Koestler and his wife, Cynthia, entered their sitting room at 8 Montpelier Square, London, sat down facing each other. He in his favorite leather armchair, she on the couch and poured themselves their usual drink before dinner,” biographer Michael Scammell begins in his well-received, Koestler: The Literary and Political Odyssey of a Twentieth-Century Skeptic (Random House, 2009). It would all end here, now, his way. He and the missus imbibed that evening a death cocktail, and were soon asleep forever.

Mr. Koestler was a Forrest Gumpian figure of the middle to late 20th century. Always involved in a rich and deep intellectual life, though manic most times, on its way to join a cause, earned cameos from lights such as Langston Hughes, George Orwell, Albert Camus; scrapes between he and B.F. Skinner and Isaiah Berlin. He even could claim to have known JP Sartre.

Author of perhaps most notably Darkness at Noon, a vivid and go-to anti-Communist novel, he was in fact a committed Communist for a solid chunk of his adult life. Something of a philanderer, married three times, he was long thought to be a progressive voice for women. The contradictions and skeletons are there.

Mr. Koestler has largely nothing to do with cryptocurrency. He wasn’t anything close to an anarchist, finding the state necessary in nearly every facet of life. At the borders of the ecosystem, however, is a lingering idea he birthed: holarchy. It derives from the word holon, coined by Mr. Koestler in his lesser known 1967 nonfiction psychological philosophy book, The Ghost in the Machine.

Crooked intellectual lines drawn straight

This strange man with strange ideas lays a foundation for Bitcoin. Without jumping too much into the polemical weeds, essentially Mr. Koestler described how in nature all material existence is both a part and whole of reality. He dubbed that tension a holon. Humans are both part of a larger society, yet would consider themselves rugged individualists, and both seemingly cannot be true and are true.

It’s downright Hayekian in the sense holons create grave complexity from emergent order. And while Mr. Koestler surely used the descriptive phrase as also something of a pejorative, his recasting of classical dualism helped fringe thinkers develop the eventual notion of holarchy. Everyone is a leader in a leaderless system, to put a finer point on it.

So crazy an idea it has actually found its way into the real world, apart from Bitcoin. Morning Star, a tomato processing company in California, practices holarchy to great success. It’s one of the largest, most profitable companies of its kind. The Morning Star Company refers their company organization as the “philosophy of Self-Management. We envision an organization of self-managing professionals who initiate communication and coordination of their activities with fellow colleagues, customers, suppliers and fellow industry participants, absent directives from others. For colleagues to find joy and excitement utilizing their unique talents and to weave those talents into activities which complement and strengthen fellow colleagues’ activities. And for colleagues to take personal responsibility and hold themselves accountable for achieving our Mission.”

If it sounds like so much corporate speak, it is not. There are no managers. Everyone is titled equally, given a budget, and works in rational self-interest with an eye toward severely limiting bureaucracy. Holarchy.

Literally no one is in charge

A mainstream treatment of the concept was given by no less than Harvard Business Review in “Beyond the Holacracy Hype,” by Ethan Bernstein, John Bunch, Niko Canner, and Michael Lee (July-August, 2016).

They spend a lot of pixels discussing in depth online clothing retailer Zappos’ integration of holarchy, styled holacracy. The authors conclude, “Using self-management principles to design an entire organization makes sense if the optimal level of adaptability is high—that is, if the organization operates in a fast-changing environment in which the benefits of making quick adjustments far outweigh the costs, the wrong adjustments won’t be catastrophic, and the need for explicit controls isn’t significant. That’s why many start-ups are early adopters.”

This idea in its most extreme form happens in Bitcoin (and by that I mean BCH). Literally no one is in charge. And while very vocal critics see that fact as a bug and not a feature, it still has managed to become arguably the best money in the history of human affairs. All these factions, groups, individuals, developers, miners, investors, merchants, holons really, make up the phenomenon.

Here’s anarchy, literal anarchic money, driven to an emergent order. How can it be? Doesn’t there need to be a Guide? A Ruler? It turns out, no. In fact, hell no. At its worse, as its most contentious, if a group or personality attempted to squeeze Bitcoin into a subjectively desired shape, the protocol is maddeningly open source. It can be forked, regrouped to survive another day.

Beautiful anarchy

How direct Mr. Koestler’s ideas were on the creator(s) of Bitcoin isn’t clear at all. But there is something to the theory Bitcoin had to come after the concept of holarchy was developed beyond Mr. Koestler’s unveiling. In any event, Mr. Koestler named the principle, even if by accident.

How direct Mr. Koestler’s ideas were on the creator(s) of Bitcoin isn’t clear at all. But there is something to the theory Bitcoin had to come after the concept of holarchy was developed beyond Mr. Koestler’s unveiling. In any event, Mr. Koestler named the principle, even if by accident.

The intellectual genealogy of Bitcoin, along with Bitcoin itself, is anarchy in action, a demonstration of holon-type thinking. Formal linkage can be made (and has) to loveable cyber-anarchists, to cypher punks, who shared these cranky assumptions. None of them liked to be told what to do, and so, maybe without even knowing it, they lived and breathed Mr. Koestler’s accidental genius.

Top-down corporate models could’ve never given rise to Bitcoin, and for good reason. A corporation is a limit on liability, a legal designation by government. It’s not necessarily a natural fact corporate structures in business as we understand them now would survive in stateless, voluntary ways of organizing society. I’d wager they would not.

Freedom is chaotic from the outside, and indeed we’re often left flummoxed by the pace of change within the anarchy of everyday life. We grope for patterns, and can often ascribe wrong causal relationships, leading us to make worse decisions in the future as a result. Instead, we should think more like what Bitcoin is: permissionless, borderless, censorship resistant, leading to a beautiful anarchy.

C. Edward Kelso is a financial technology journalist based in Southern California. Follow him on Twitter.

02-27-2026

02-27-2026