|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

The Coinbase IPO is actually a direct listing and is set to go live on April 14, demonstrates that we are currently at an awkward phase in the digital asset story, caught between two distinct eras.

On the one side, in the past, there is a chaotic infancy where early adopters scrambled to cobble together important ecosystem infrastructure largely outside the notice of the mainstream and especially the legal system.

On the other, stretching out ahead of us, is an inevitable future in which the digital asset industry has reached maturation: our service providers are compliant and watched carefully, our lawmakers have adapted or introduced legislation where necessary and regulators and law enforcement the experience to pursue bad actors in the same way they would in any other industry.

What we are seeing in the industry is the transition between the past and the future. Though many of the earliest and most lawless service providers have gone extinct (think Mt. Gox, or Charlie Shrem, or Binance, which as recently as last month was announced to be under investigation by the CFTC), some of the pillar companies of the digital asset community are holdovers from this period.

Coinbase (NASDAQ: COIN) is one of those companies—and they’re asking you to give them your money.

Buying into a race to the bottom

As long as there has been talk of a Coinbase IPO, there has been excitement. After all, Coinbase is the largest digital currency exchange in the United States by volume with excellent brand recognition across the world. To invest in Coinbase, supposedly, is to be able invest in a pillar of the ecosystem—for the first time in the history of the industry.

Though Coinbase’s market position goes someway to explaining its gargantuan US$100 billion valuation, it does not explain everything. The IPO is coming at a time of unprecedented investment activity from demographics who were previously absent.

The most proximate cause for the excitement (and valuation) are Coinbase’s reported financial results. Coinbase released ‘preliminary’ and ‘unaudited’ first quarter results for 2021 a week ago, which built already-bloated revenue expectations to even more absurd heights. The Q1 revenues showed 9-fold increase in revenues to $1.8 billion compared to the same period last year, and up from the $1.3 billion generated through all of 2020.

Based on Coinbase’s reported revenue breakdown in 2020, $1.5 billion of this comes from transaction fees. These revenues, and the revenues being forecasted in justifying Coinbase’s extraordinary valuation, are based on Coinbase’s current fee structure, which can run as high as 10% per transaction. Coinbase’s S-1 filing indicates an average transaction fee of about 0.5% in 2020.

To illustrate how high these fees are, compare this to the long-standing Nasdaq Inc, which owns the Nasdaq as well as Philadelphia and Boston Stock Exchanges. According to Fortune, the average fee for each trade is 0.01% on the dollar.

Nasdaq Inc is operating in a field which is far past the point of maturation and where the equilibrium is relatively well entrenched. While direct comparisons will never be perfect, it seems plainly obvious that Coinbase is a fat target for competitors who will be able to easily compete with Coinbase on price. There seems almost no chance that Coinbase’s fees are ever as high as they are now, and yet this is the assumption that people seem to be making in justifying Coinbase’s massive valuation.

Coinbase has enjoyed a lot of room at the top, purely because so few other companies in the industry last long enough to grow as large as Coinbase has without being crippled by some scandal or another. The fees are high, but reliability is everything to an exchange, and escaping significant regulatory action for this long is about all it takes to be considered reliable in this industry.

These days are coming to an end. Regulatory and legislative attention are slowly purifying the digital asset lake at a time where the industry is in the mainstream like never before. Competition is going to come thick and fast and will have plenty of room to out-maneuvre Coinbase in terms of fees. At the same time, these new companies are becoming less vulnerable to the great regulatory filter that has hitherto been protecting Coinbase.

So, what would Coinbase look like in a word where its fees are comparable to that of the Nasdaq? If Coinbase’s average fee for the first quarter of this year was 0.01% rather than 0.5%, Coinbase’s revenues would drop from $1.5 billion to less than $40 million.

In other words, the Coinbase IPO is an offer to buy into a race-to-the-bottom that hasn’t even started yet.

Skeletons in the closet

Not only will Coinbase’s competition be able to compete purely on price, but they’ll have a marked advantage in another way. The ‘great regulatory filter’ talked about above has protected Coinbase, but purely by accident.

Coinbase is like planet Earth, floating through the universe, thriving while other planets are wiped from existence by traveling asteroids and other celestial dangers. But just because Earth has managed to narrowly escape collision with a passing comet or happened to survive the disasters that have come its way does not mean that an asteroid or even asteroids are not currently on a collision course with our planet, waiting to annihilate us at some future date.

The same is true of Coinbase. Founded in the same era where BitConnect was allowed to operate as a pyramid scheme with little scrutiny, it is a pure accident that Coinbase was not crippled by some scandal or another long before it reached its current level of dominance.

In fact, Coinbase has been confronted with a number of serious accusations over the years, up to and including last month.

There are accusations of insider trading. There are ongoing questions over Coinbase’s decision to list XRP, which the SEC is currently pursuing on the basis that it is an unregistered security. Coinbase faces a class action suit over the matter on the basis that they were aware that it was listing an unregistered security and had therefore defrauded investors who had bought the asset. Coinbase is often hit with complaints of unexplained outages during the most significant price movements.

It is not as though Coinbase’s preparation for its public offering can alleviate any concerns, either. In fact, Coinbase was being punished by regulators as recently as last month. The CFTC fined Coinbase for artificially inflating trading volumes by trading between its own entities.

In October 2020, Coinbase’s chief compliance officer Jeff Horowitz left the company, the timing of which raises eyebrows considering how close the company was to its IPO at that stage.

Horowitz’s departure came loosely around the time of a broader and more earth-shaking revelation. An exposé by the New York Times not four months ago exposed employee discrimination on the basis of both race and gender. For example, women were paid 8% less than men in similar roles, while Black workers were paid 7% less than non-Black employees in comparable roles. The New York Times also reported that three-quarters of Coinbase’s Black employees quit through late 2018 and early 2019, with 11 complaining of racist or discriminatory treatment which was not actioned by management, including instances of open racism.

One of the employees had this to say:

Most people of color working in tech know that there’s a diversity problem…But I’ve never experienced anything like Coinbase.

Though the U.S. equal employment opportunities regulator, the EEOC, has yet to take action and though it seems no lawsuits have been filed, the New York Times pointed out that Google and Oracle had been sued for discrimination over a pay gap that was half that being reported within Coinbase.

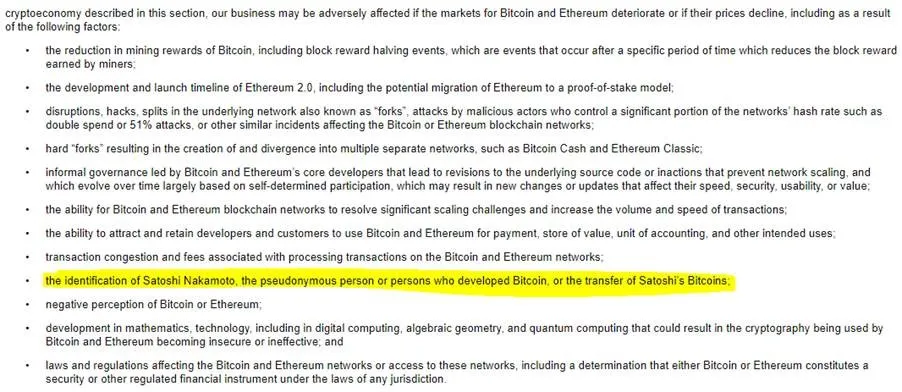

Coinbase is worried about Satoshi Nakamoto

In Coinbase’s S-1 filing, a mandatory disclosure form which must be submitted to the SEC by any company wanting to go public, they list a number of factors which have the potential to adversely affect their business. Naturally, the health of the digital asset market(s) is a major factor, but Coinbase identifies one in particular worth mentioning:

“…the identification of Satoshi Nakamoto, the pseudonymous person or persons who developed Bitcoin, or the transfer of Satoshi’s Bitcoins…”

This is intriguing by itself. Most organizations in Coinbase’s position expend great effort to downplay the sword of Damocles hanging over the head of the market—namely, that the return of Satoshi Nakamoto and the potential release of billions of dollars’ worth of Bitcoin could be catastrophic for the market.

The timing of this inclusion invites consideration, given the burst of activity by Dr. Craig Wright in the last year in combating those who have called him a fraud and attempted to discredit Bitcoin SV, including the well-publicized delisting attack on BSV by a number of exchanges.

Ownership of the White Paper? Mr. Wright, if you say it, show it. @coinbase is proud to support @opencryptoorg in shining a bright light on this dubious claim. https://t.co/9YxNPQU7d6

— paulgrewal.eth (@iampaulgrewal) April 12, 2021

Buying exposure to scandal

This smorgasbord of controversies—some as recent as last month—should be troubling as Coinbase prepares to go public. Certainly, the kinds of crisis common to the industry have the potential to sink a company all by themselves. A single hack was enough to spell the end for Mt Gox, well before the much more damning suspicions over Mt Gox’s involvement came to light.

Coinbase might now be big enough to withstand many scandals that would have wiped out smaller organisations. However, when a company is public, the investors—many of whom will be retail—get direct exposure to the impact of these scandals—and companies within the digital asset industry are hit with a staggering number of scandals and criminal accusations compared to other industries. While these have certainly received media coverage and public interest, the only measure of their impact has been where it has been large enough to sink the company entirely. More often, the public only gets drabs of information leaked to the press, or if they’re lucky, a balance sheet to pick over and compare against pre-scandal earnings.

But as we have been told repeatedly: Coinbase’s IPO is the first of its kind. Already a lightning rod for controversy, the company is about to have a share price open for all to see. On the flipside, on 14 April, countless people are going to—for the first time—be able to buy exposure to a company that is not only currently embroiled in scandal, but might get blown up by a number of investigations or accusations at any moment.

One might imagine that the public’s tolerance for the wild west that crypto has become will be much lower when their pockets are being hurt directly by the problems such a circumstance creates. Likewise, public companies attract scrutiny—not only from the public, but from law enforcement and regulators—to a degree not typically seen in purely private companies flying further under the radar.

On top of all of this, Coinbase is operating in an industry where the future of regulation is an entirely open question. If comments by the U.S.’s incoming administration are anything to go by, the other shoe is going to drop on the industry sooner rather than later. Just how can Coinbase be fairly valued without knowing what regulatory equilibrium will look like?

Even assuming there is no major existential scandal in the near future, everyone needs to ask this question: What will the CoinBase model be worth when this industry is fully regulated, competition forces margins down and it becomes generally understood that they are intentionally not exposed to any token platforms that actually scale?

Perhaps Coinbase is not such a good deal after all?

09-18-2025

09-18-2025