|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

This post originally appeared on Elas.Digital site and we republished with permission from the Elas team.

Improvements on current systems include that there is only one electoral roll per electorate, removing the possibility of anyone voting at multiple booths. Non-voters can be traced by the electoral authority, but because the ballot is handed to them only after their voter token has been transferred, we keep a strong chain of security around the voting process without sacrificing user privacy.

A great example of this is in the electoral ballots that we use every few years to elect politicians to office.

Currently, in Australia the process is such that you must present yourself at a polling place either prior to (limited locations) or on the day of an election and have your name marked on the Electoral roll as having voted.

In this post, we will look at how Elas tokens can be used to make two parts of this process much more secure without sacrificing any of the privacy users currently enjoy in their ability to vote.

Election ledger

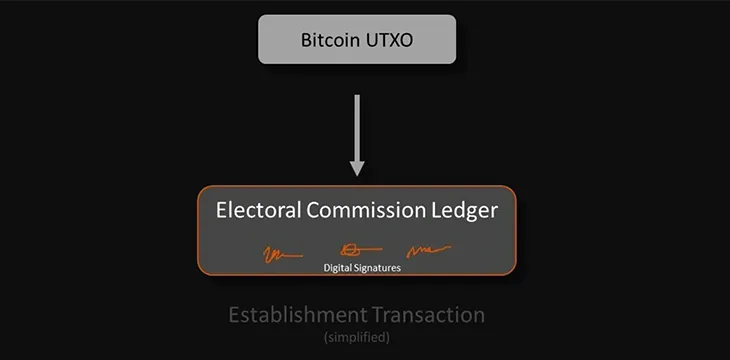

The electoral commission in the country where the vote is being cast establishes their own ledger in a single action.

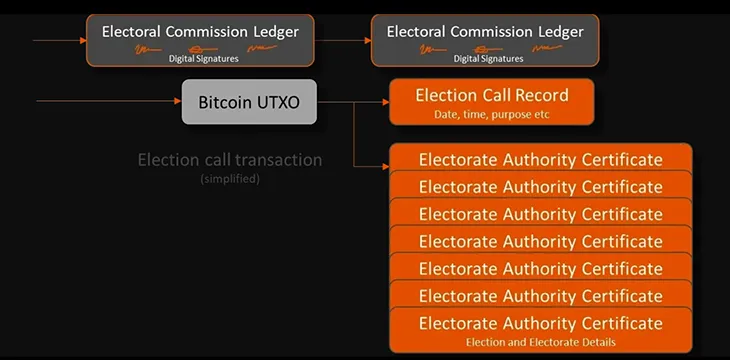

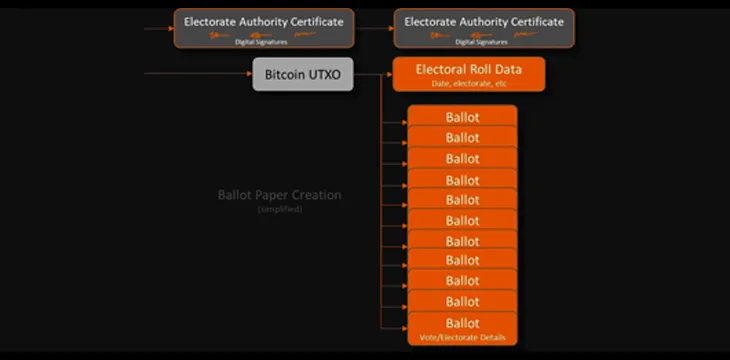

Inside this ledger, Election Call Certificates are issued which each are used to generate an election specific sub-ledger each time an election is called by a political leader. Within that subledger, each electorate receives an authority token which will be used to print the electoral roll and ballot papers for that zone.

Election setup

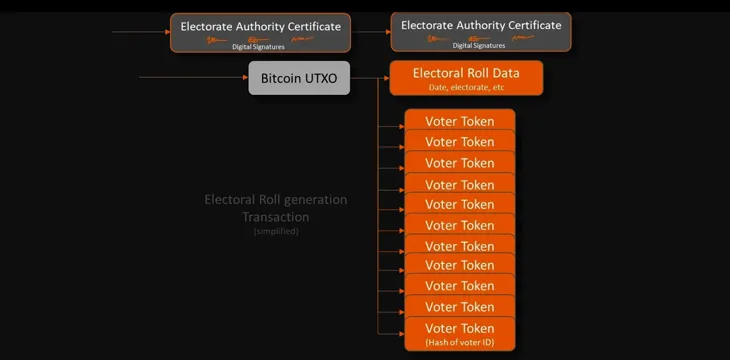

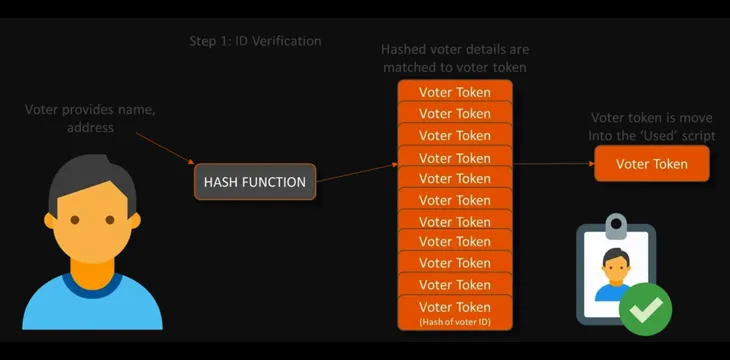

When an election call has been issued, each Electorate Authority certificate is used to issue tokens for each voter being on its associated electoral roll. These voter tokens are private, but can be tied to each voter by anyone with high level access to the Electoral roll’s digitization details or with a specific voter’s details. The voter tokens are spent into a script that indicates the represented voter has not yet voted.

Second, the Electorate Authority certificate is used to issue a series of ballot papers. These are separate to the voter tokens and carry only the details of which election they are being used in and which electorate they are for.

The ballot papers are printed into a script that requires two knowledge proofs to transfer. One is held by the electoral authority for that electorate, and one is printed onto a piece of paper and sealed in such a way as the proof cannot be exposed without destroying the packaging. Adequate ballots are printed such that extra physical copies can be made available at each polling booth to ensure nobody runs out.

Voting process

At this point, the polling stations can now be set up.

Whether they are early votes or votes on the day, the process is the same. Each polling location has two zones, one of which manages the voter ID checks, and one which hands out ballot papers. As each voter presents themselves to the ID check, they give their details to an electoral roll checker. The checkers have access to a web app which is able to find the user’s particular token if the user presents their correct details, and which spends their voter token into a new script to indicate that they have voted.

The spending of the voter token into the ‘Used’ script shows that the voter has taken part in the election and prevents them from attending other polling booths and voting multiple times. If the voter’s name or address aren’t correct, the hash function will not correspond to any voter token. This means that the agents managing the ID process never see the full electoral roll and are only exposed to the details of the voters they directly process, maximizing user privacy.

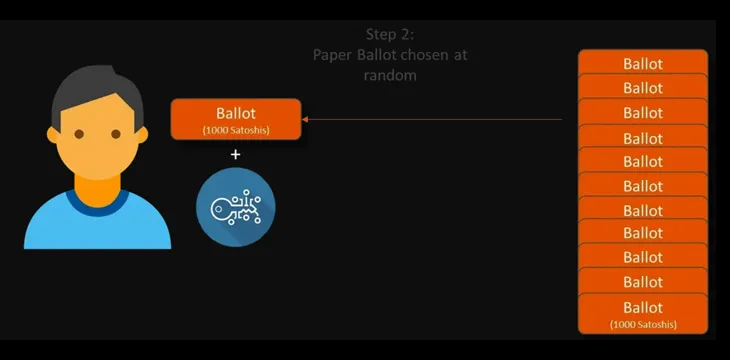

Once the voter’s token has been moved, the voter is handed an envelope with the knowledge proof needed to cast their ballot.

Once handed a valid ballot paper, the user would use a secure web-app to cast their vote. Because the knowledge proof is on the ballot, this is something that can be cast from any device that can capture a physical image of the paper and translate its contents, which could be in the format of a QR code, barcode or NFC device.

The user would scan the ballot paper which would take them to a voting interface that would allow them to cast their vote. The vote is written onto the ballot paper which is added as an input to a large transaction held by that electorate authority which is completed when the polling is over, at which time the full transaction is signed and spent onto the Bitcoin ledger. This keeps any votes that have been cast from the public eye, but allows anyone who kept a record of their ballot’s serial number to be able to audit that their vote is present in the final tally.

Improvements on current systems include that there is only one electoral roll per electorate, removing the possibility of anyone voting at multiple booths. Non-voters can be traced by the electoral authority, but because the ballot is handed to them only after their voter token has been transferred, we keep a strong chain of security around the voting process without sacrificing user privacy.

Watch Brendan Lee’s presentation at CoinGeek Live 2020 Day 2.

09-05-2025

09-05-2025