|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

BitFlyer has announced that they will force liquidation of all their customers’ Bitcoin SV (BSV) coins that have been held in custody since the fork of BSV from BCH more than a year ago. For over a year, customers of the Japanese exchange have been unable to access their BSV assets which were created in a 1:1 ratio to all their BCH holdings after the ledger splitting hard fork where the BSV project diverged from BCH due to ideological and technical disagreements between development teams.

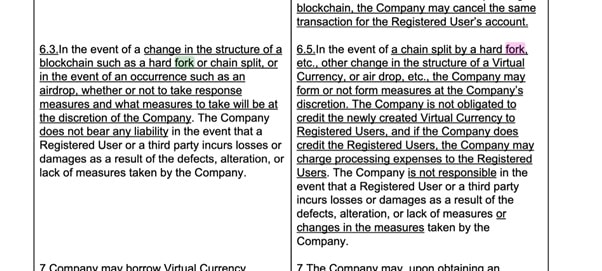

BitFlyer makes this announcement, just less than a month after they posted new Terms & Conditions service which all users needed to accept upon logging in which basically state that BitFlyer has the right to credit or NOT to credit users with the forked assets which were created as a result of a ledger split, or just liquidate the assets and reimburse users in JPY and that the company has the right to charge the users fees for the liquidation. Basically, if users accept the changed terms and conditions (updated Nov 19 2019), they give BitFlyer the right to sell all their BSV assets (which have been locked up for over a year now—long before BitFlyer’s attempted new terms service were even created), and be charged for the trouble.

Customers have little choice though, if they don’t accept the new terms of services, then they won’t be able to login to their account at all. By trying to change its terms of service just before announcing its unilateral decision to force liquidation of customers’ BSV assets, BitFlyer is retroactively trying to impose on customers new legal terms that did not exist at the time of the BCH-BSV hard fork. This raises serious questions about whether BitFlyer’s attempted actions are legally enforceable.

Where BitFlyer may run into legal murky waters is determining which coin was the ’new’ coin and which coin was the old coin in a hard fork. There are different ways to look at the issue and it isn’t all that clear which perspective a court will consider. Does the ticker symbol decide which is the original coin? But then the exchanges determine what ticker to give any new crypto asset, and certainly there is a measure of collusion or consensus that is involved. At least that is what we saw at the last hard fork between BCH and BSV, where BCH developers and proponents have openly admitted that they approached all the major exchanges previous to the hash war to ensure that they would give BCH ticker symbol to the Bitcoin ABC node client. The other way to look at which coin is the original is the coin which preserves the feature set closest to the original design as defined by the creator. Therein lies the issue, as Bitcoin was created with a pseudonym it is not as easy as just asking the one who owns the copyright. Or is it? Dr. Craig Wright has successfully registered copyright of the Bitcoin whitepaper in 2019, and there is certainly a lot of controversy surrounding the self-proclaimed creator of Bitcoin.

By way of comparison, it was the Ethereum community which first demonstrated that the legacy protocol for a blockchain project could be issued a new ticker symbol even though it represents the original approach. In 2016, Ethereum implemented a hard fork in its code in order to restore 3.6 million Ether tokens that were stolen in June 2016 from The DAO venture capital fund. This move was done after a vote and “rolled back” the Ethereum chain and transactions to their state before the theft of DAO tokens. Some Ethereum community members rejected this hard fork on the principle that the blockchain should not be subject to change in this manner, and decided to keep using the original “unforked” version of Ethereum. This created a competing Ethereum chain, which acquired the new name Ethereum Classic, and was issued a new ticker symbol ETC used by exchanges. But Ethereum Classic actually represents the original Ethereum protocol, even though it uses a new name and new ticker symbol. It was in fact the other chain that actually forked away from the original protocol, but managed to keep the original Ethereum name and ticker symbol. In this kind of situation, would BitFlyer decide Ethereum Classic (ETC) is a new token and forced liquidation of its customers ETC tokens, even though they represent the original Ethereum protocol?

The entire situation highlights why exchanges should not be the deciders of protocol battles and what coin best represents the legacy versus new protocol rules after a hard fork. One thing is for sure, once the smoke clears, and if Dr. Wright chooses to enforce his copyright over the Bitcoin white paper and most of the early Bitcoin code, and claim all other forks of the projects as just attempts to ‘pass off’ as Bitcoin, then BitFlyer’s own Terms and Conditions will work against them. Because it will be that BSV is the original coin, and the newly created coins would be BTC and BCH, and they would have liquidated the wrong asset of all their clients.

BitFlyer’s new Terms and Conditions which users must accept, updated Nov 19, 2019—one year after the BCH-BSV hard fork, presumably in preparation to force liquidate all their customers BSV coins.

Of course, even for an exchange that does not want to support BSV trading, the safer option would simply be to give customers access to withdraw or trade their BSV coins, so that BitFlyer won’t be responsible for the forced liquidation of the wrong assets of their clients. So why doesn’t BitFlyer just return the BSV to the customers?

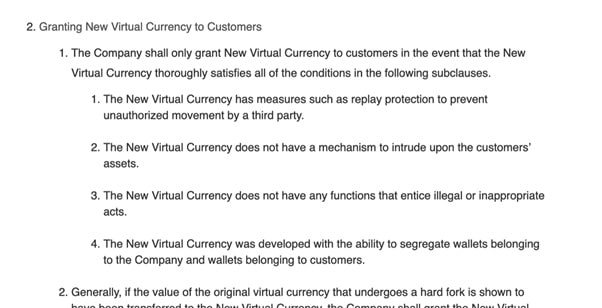

Ostensibly, they claim it is because BSV fails to fulfil the requirements to be supported as a new fork coin.

BitFlyer strictly wants replay protection for a new coin to be supported. But replay protection on the protocol level has legal ramifications.

Considering the 4 stipulations put forth in this clause, the only one which applies to BSV is #1, the lack of replay protection. This is surprisingly the same reason that Coinbase purportedly refuses to support BSV. And it is a facetious reason. Replay protection only matters in the period immediately after the actual fork. After the two competing chains have sufficient blocks and proof of work built after the hard fork that are not in common, there is little chance of any accidental mixing. More importantly though, the desire to split one’s own coins is something that each user needs to make on their own. Because splitting your coins after a hard fork may have taxable consequences (as does any airdrop of coins), this is not a decision which an exchange can or should make on behalf of a user unknowingly. A user who splits his coins, decides to acknowledge the new asset and the new income that may come with it (i.e., the monetary value of the new coins at the moment the user receives access to the new coins). If a user wishes to NOT acknowledge a hard fork (as many hard forks of minor coins are not worth dealing with) they should not have to do anything, and they will not trigger any tax event. Much of how forks affect taxable income, and also what is legally the ‘legacy’ coin vs the newly created coin is explored in detail in Dr. Wright’s (who holds a masters in law) blog post on hard forks and their effects on taxes.

The point is that replay protection forces everyone’s coins to be split, causing everyone holding “new” coins to incur potential tax events. This is not something that protocol developers should be doing, so BSV teams have thus far declined to add replay protection. If a user wants to split their coins, then they can using wallet software. If they don’t, and they send both BSV and BCH when they try to deposit BCH to an exchange, the exchange should just do what they should do whenever someone accidentally deposits money into a wrong bank account. They should hold it, determine the mistake, and refund the coins. To push the responsibility to protocol developers to split the coins at the protocol level is just plain lazy and irresponsible.

More practically, the BSV network has operated separately from BCH for over a year—without any problems from the lack of replay protection.

We hope that BitFlyer reconsiders their position, and return the BSV to their customers if they choose not to support BSV trading because of their policies. For the good of their clients, and to avoid challenges to the lawfulness of their actions, in the event what turns out to be the ‘legacy’ asset and which is the ’new’ asset in a fork is flipped and they find themselves in murky legal waters with a lot of angry customers at their doorstep.

02-23-2026

02-23-2026